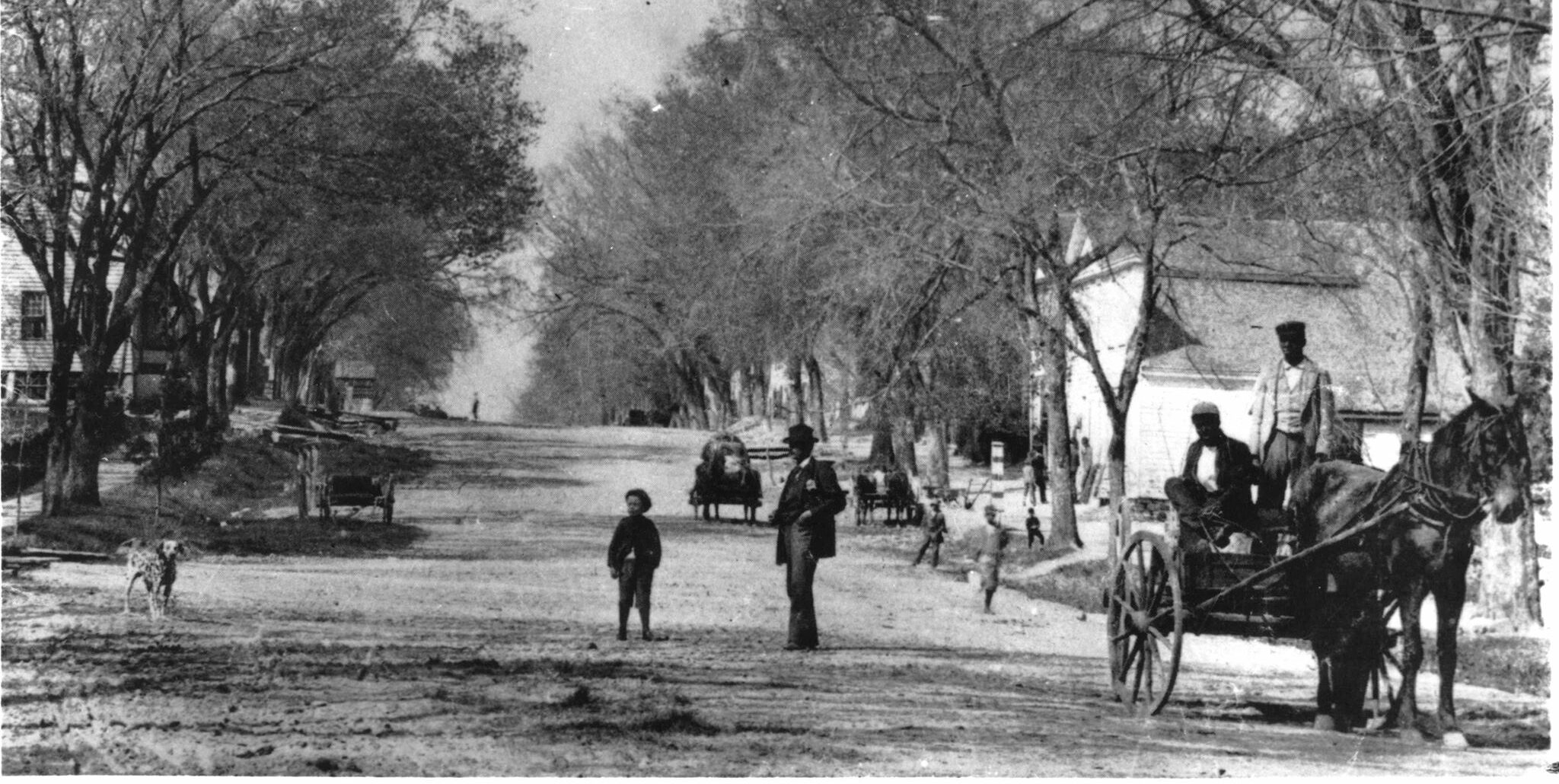

When Franklin Street was officially named in the 1790s, after the newly deceased Benjamin Franklin, planners had no way to imagine that the street that would become the central attraction of Chapel Hill or that it would one day need to accommodate the cars of thousands of locals, students, faculty, staff, and visitors. The road was unpaved, constituted of dirt and therefore prone to flooding and severe muddiness, especially in the spring months. It wasn’t until the Good Roads Movement—a mostly rural advocacy campaign supporting the paving and maintenance of roads—took hold in the area that Franklin Street was paved, which it eventually was in 1921.1

A boy sits in a box on a flooded, pre-paving Franklin Street sometime between 1910-1919, via the NC Collection Photographic Archives.

With the roads paved, Franklin Street grew exponentially. Just a year later, in 1922, Carolina Coffee Shop became the first restaurant directly on the street. Angled parking spots were marked on the sides of the road, which at the time was far wider and has since narrowed to increase space for outdoor seating at restaurants, pedestrians, and sidewalk accessibility.

Several service stations were created in the following decades to cater to the influx of cars now passing through. The first appears to have been a Texaco service station constructed in 1927, although the ownership was transferred the next year as the building became The Southland Motor Company, which both sold and repaired cars and necessitated the construction of an additional garage in the back to cope with demand. The structure was demolished in 1966, and the space is now home to a parking lot.2

Another Texaco service station was constructed in 1930-31, a small Neoclassical building operating under the name University Service Station before it was eventually demolished in 1992. The land is now home to the modern Top of the Hill building.3 A third service station was constructed on West Franklin Street and operated as the Phillip Andrews Service Station upon its construction in 1949, selling Gulf oil products and remaining a Gulf station until 1988.4 With all of this additional infrastructure to support the driving population of Chapel Hill, many possibilities for Franklin Street opened up—such as the possibility of hosting a parade.

University Service Station circa 1940, via the UNC-Chapel Hill Wilson Special Collections Library.

The first official Beat Dook Parade was held on November 19, 1948, though versions of it existed as early as 1933. At the time, Franklin Street was wider, with angled parking spots instead of the parallel ones that line it today. A Daily Tar Heel article about the event recounts that 28 cars and floats went down Cameron Avenue, carrying beauty queens selected from the sororities and fraternity brothers acting in the role of “Duke medical patients” receiving medical treatment for their game losses.5

Starting in 1949, however, the parade was conducted on Franklin Street, and several local high schools contributed with their own floats—and beauty queens. The tradition began with the Pi Kappa Alpha fraternity, who established the parade to encourage school spirit and festivities leading up to the game. It featured celebrity judges that gave out awards, a full schedule of events pre-published by The Daily Tar Heel, and a massive bonfire on the football field. The parade remained in some capacity until 2000.6

Click here to see a short video of the 1950 parade, shared by the UNC-Chapel Hill Wilson Special Collections Library on Facebook.

The Beat Dook Parade rolling down Franklin Street in 1949, via the NC Collection Photographic Archives.

Photos of the Beat Dook Parade from the 1974 Yackety Yak, via the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center.

Lincoln High School, Chapel Hill’s segregated high school for African American students, also participated in the parade down Franklin Street, sending their own beauty queen in a float alongside the sororities.

Lincoln Junior High’s beauty queen on her pageant float, via the NC Collection Photographic Archives.

Another legendary aspect of Franklin Street sports culture comes after the game. The first documentation of students rushing Franklin Street comes from a 1957 edition of The Daily Tar Heel, recounting how thousands of students and spectators swarmed the area after the basketball team’s win over Kansas, securing them an NCAA title. The situation quickly dissolved into chaos—a car accident led to two arrests, a stoplight was taken down, and an enormous bonfire was built.7 This was the first of many disorderly Franklin Street rushes—a tradition that continues today. The fires are as much a part of the celebration as Carolina blue. These celebrations have only grown with time, as UNC’s 2017 NCAA championship win shows us. An estimated 55,000 people rushed Franklin that night, as depicted in several timelapses of the event.

A crowd of around 15,000 rushing Franklin Street on March 9, 2022, after UNC beat Duke in the Final Four of the NCAA tournament, via Peyton Sickles for Chatham News and Record.

The most famous of North Carolina’s players are also intertwined with Franklin Street—here they came to drink, eat, after parties and games and during practice breaks. Eddie Williams, owner of Time Out on Franklin Street, remembers with fondness Michael Jordan coming into his restaurant during his years as an undergrad in North Carolina. He was polite and very respectful, but had a competitive streak—he would play pool with fellow players at several of the bars around and would “die to win,” according to Eddie. On the wall of Time Out, now located much further East than it was when MJ was a student, hangs a photo of the basketball legend making the “time-out” symbol with his hands, staged as a favor for Eddie.

Michael Jordan with his new Mercedes in August of 1985, photographed by Sam Kittner. He’s wearing first-generation Air Jordans.