It’s the big night of a big Duke game. Up and down Franklin Street, throughout Chapel Hill, and across the entire state of North Carolina, Carolina fans crowd into sports bars and living rooms with eyes locked on the screen for one of college basketball’s most iconic rivalries. Everyone’s buzzing, hoping for the moment – the final buzzer, the win, and the mad dash to Franklin Street.

While this is one of UNC’s most electric and recognizable traditions, it’s far from the only one. As the nation’s first public university town, Chapel Hill is steeped in history and ritual. From Rameses, the fuzzy mascot who “jumps up jumps up and gets down,” to quirky campus organizations like the Carolina Cheerios, some traditions are loud while others hum quietly in the background.

What remains true across the board? Franklin Street is – and always has been – a heartbeat of Carolina pride that pulses with energy, is layered with history, and breathes with every chant, cheer, and tip-off.

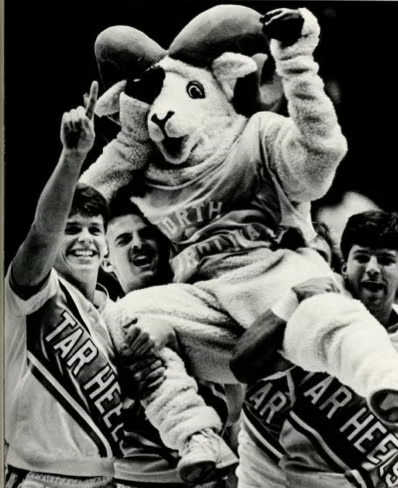

Rameses

It’s hard to imagine today, but Rameses, the fluffy mascot with gold horns and exuberant UNC spirit, did not bless Carolina basketball games until the mid-1980s. The story of the live ram goes back even further. In 1924, head cheerleader Vic Huggins determined that the university teams needed their own mascot. In a conference where North Carolina State had a wolf and Georgia a bulldog, it was obvious what a symbol of the institution could do for spirit. As football as an American institution and UNC’s football team steadily gained notoriety, it made sense to introduce the new mascot at a football game day. The problem? Choosing an animal.

According to legend, the mascot was chosen by head cheerleader Vic Huggins as a reference to star fullback Jack “The Battering Ram” Merritt. Rameses I was shipped from Texas, bought for a whopping $25, just in time to make his first appearance at a pep rally held before a VMI matchup. When kicker Bunn Hackney rubbed the ram’s horns for good luck before scoring the game-winning field goal, Rameses was solidified in Carolina lore. For nearly a century and through 21 generations of rams, the Hogan family has lovingly cared for UNC’s live mascot, guarding him from rival kidnappers, grooming him for game days, and preserving a cherished Tar Heel tradition that unites generations of fans.

The costumed mascot version of Rameses slid across the basketball court for the first time in the 1980s. Until this point, Carolina was the only team in the ACC that did not have a mascot who attended games. The first suit was made with clay horns and a very smiley face, with the first Rameses costume wearer, Eric Chilton, saying it “looked like a very disgruntled lamb.” In the following years, the mascot was reinvented to fit the needs of the sports sphere. Rameses is a crowd favorite who loves Carolina athletics first and foremost, jumping around and engaging with fans at any opportunity. In 2015, RJ (Ramses Junior) joined the line-up to expand school spirit – RJ is smaller, meant to appeal to the younger Carolina fanbase while also allowing for more fan engagement. There have been several iterations of the mascot before the modern and well-beloved edition, but all iterations of the iconic ram will go down as vessels of UNC pride.

Photograph from the Yakety Yak, 1988

See: Our State Magazine, “Meet the Family that Takes Care of UNC’s Mascot,” Tar Heel Blog, “History of UNC’s Mascot Rameses,” and UNC-Chapel Hill, “The story of Rameses”

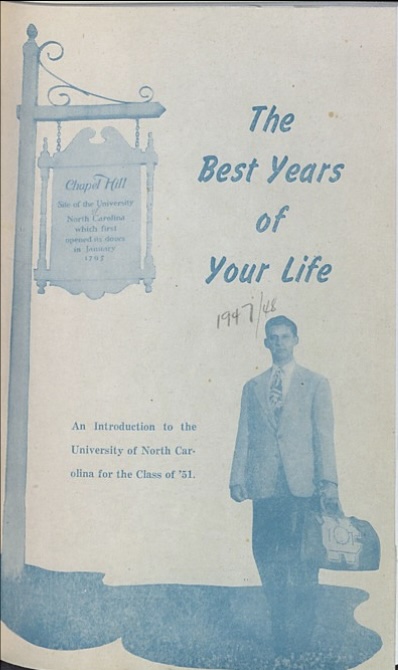

Carolina Blue and White

Few schools or towns are as identifiable by a single color as the University of North Carolina and Chapel Hill are to Carolina blue, but how did these iconic colors come to be? The DiPhi society, founded in 1795, is the oldest student organization on campus. The group was originally composed of two separate entities – the Dialectic Literary Society and the Philanthropic Literary Society, which were historically rivals. Until 1870, every student on UNC’s campus was required to join one of the two groups. Traditionally, students from east of Chapel Hill joined “Phi,” and those from the west joined “Di.” Significantly, each group had their own colors, Philanthropic represented by white and the Dialectic its sky blue. Throughout the 19th century, these colors were used to decorate campus events such as commencements and dances, steadily embedding them into the social fabric of the university. The societies eventually combined, creating DiPhi. By the arrival of intercollegiate football in the 1880s of the century, it only made sense to make the team and the university’s colors the same as the colors that had grown to represent campus culture. And thus was born Carolina Blue and White.

Photograph fromDigitalNC, “The Carolina Yearbook”

See: The Chapel Hill Bicentennial Commission, “A Backward Glance: Facts of Life in Chapel Hill”

The Carolina Cheerios

As the culture of sports in the intercollegiate sphere grew in popularity at UNC in the early 20th century, so did the need for both dedicated sporting spaces as well as a formalized way to communicate school spirit. Emerson Field was completed in 1916 (in the space that is now “The Pit”) to be used for football, baseball, and track. Football crowds quickly outgrew the space allotted by Emerson, and Kenan Stadium was opened in 1927 in a naturally occurring ravine to the south of main campus. The enormous seating sections provided by Kenan allowed more UNC students, alumni, and Chapel Hill locals to attend games than ever before – but it also meant that cheers, which had provided so much spirit and camaraderie among players and students, were growing increasingly harder to hear and lead. To get a grip on the lack of rallying coming out of the stands, student Kay Kyser established a cheering section known as the “Carolina Cheerios.” The first season, the Cheerios were a squad of nearly 250 men, bringing school spirit to the forefront of football as they led pep rallies before every game and cheered on players from the sidelines. He was joined by Vic Huggins – the same student responsible for the purchase of Rameses I, and who also went on to open Huggins Hardware which would soon become a shopping destination for the community. Kyser gained some fame himself, becoming a renowned American bandleader and television personality, spending the rest of his life in the town of Chapel Hill.

We often take Carolina’s cheerleaders for granted, but this student-created organization is responsible for the collective cheers the stands participate in and wear smiles while doing it, regardless of the outcome of the game.

Photograph from the Kay Kyser Yearbook Collection

See: North Carolina Collection, “Kay Kyser Collection: Box 92”

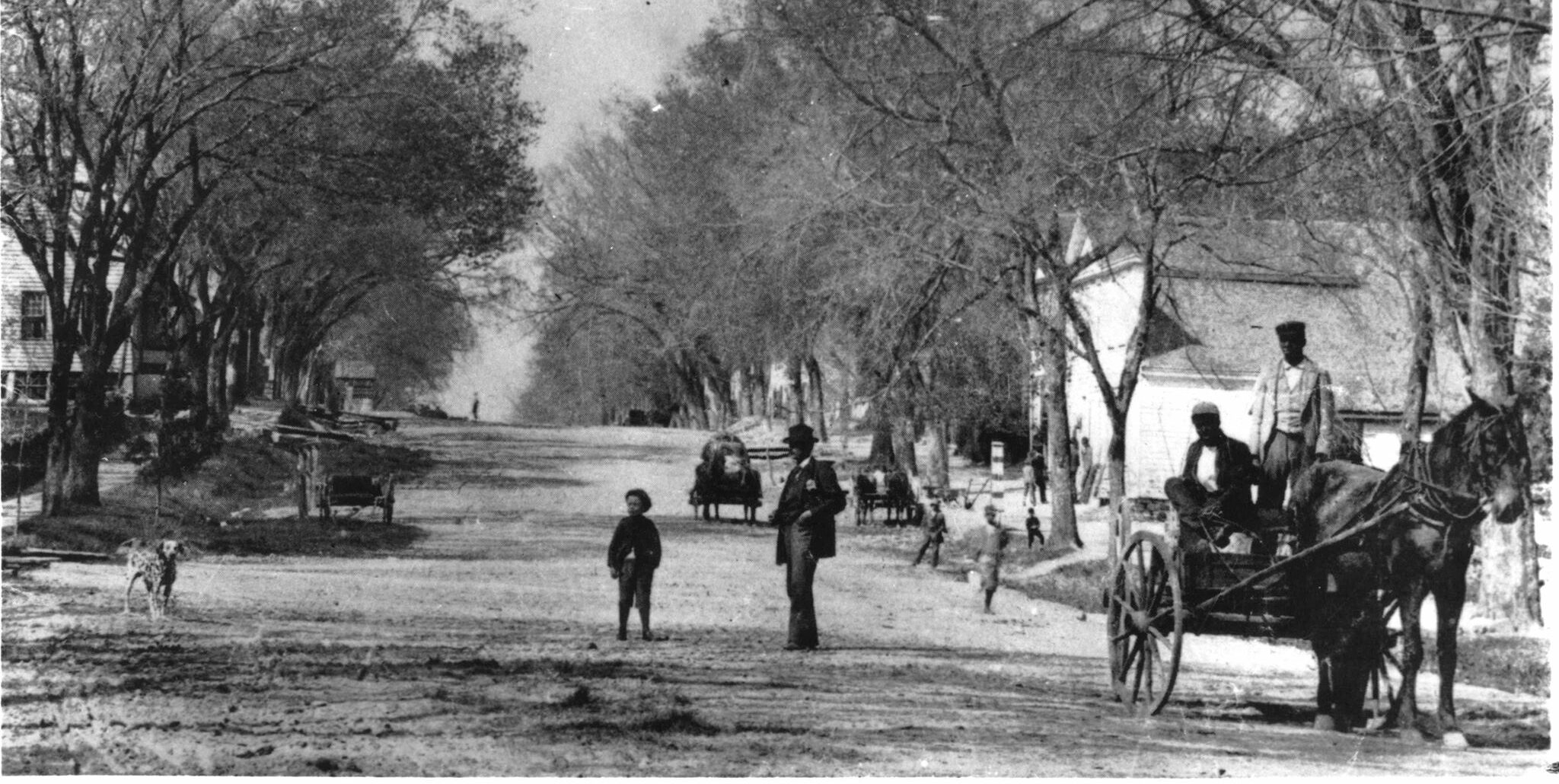

The “Beat Dook” Parade

The notorious Duke (or as it is known in Chapel Hill, Dook) vs. UNC rivalry game was first played in 1920, generating increased interest as the decade progressed due to the proximity of the two institutions, located less than 10 miles away from each other. As time went on, the game was anticipated more and more, especially by young fraternity men who were seeking any opportunity to celebrate. In the late 1930s, one UNC fraternity came up with a brilliant idea – an idea that included a parade. This philanthropy event would encourage sororities, student organizations, and local businesses to enter floats into a parade, with the best sorority entry being awarded the “Queen of the Parade.” The event quickly took off, with local Chapel Hill residents remembering the excitement the event inspired. Young families and students alike would crowd the streets of Franklin, jumping at the chance to grab candy thrown from floats or waiting for someone to lift them onto the small platforms to give their best Miss America waves. The parade usually began at Woollen Gym, where it would travel up Franklin and conclude somewhere on campus to be proceeded by a torch-lit bonfire and subsequent pep rally.

The event continued for nearly 60 years, growing and eventually becoming a part of UNC’s Senior Week celebrations before fading into obscurity in the late 1990s. The Beat Dook Parade is a prime example of how Franklin Street and the university seemingly blend together for the spirit of Carolina and the history of its community.

Photograph from the Daily Tar Heel Archives

See: UNC A to Z, “Beat Duke Parade”

Rushing Franklin Street

Tar Heels have been rushing Franklin Street since basketball became synonymous with the college campus in the 1950s. Traditionally, students rush to Franklin after the basketball team wins the national championship or beats their #1 rival, the Duke Blue Devils. Although this tradition can be traced in handwritten accounts back to the Tar Heels first NCAA tournament championship in 1957, some Chapel Hill locals can remember the tradition beginning as early as the 1930s. The scene on Franklin after a win is one of pure jubilation and giddiness, as students scramble up the hill and to the downtown district, where they swarm the streets, lighting fires, climbing poles, and climbing friends’ shoulders to see the festivities better. While Franklin Street rushing is now a sanctioned event by the town of Chapel Hill, which closes the street to traffic and stations emergency vehicles around the street, the revelers were not always welcomed by those who worked to provide a family-friendly atmosphere. Over time, the scene has become more respectful on behalf of both parties, but the tradition remains one of the strongest in the minds of UNC students and alumni alike, with generations of Tar Heels regarding the celebration as their favorite memory from their college experience.

Photograph from Raleigh News and Observer